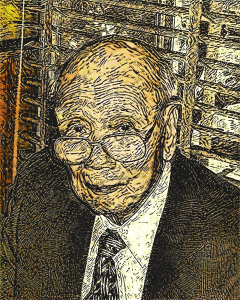

Ng Tin Sheung (1913-2012)

On this Father’s Day, 2023, I’d like to share two excerpts from my forthcoming novel about the Chinese immigration experience through Angel Island in the early 1900’s (Bridge Across The Sky, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Fall 2024) that were inspired by memories of my father.

The opening stanza of the novel is based on the only story I ever heard my father tell about his younger days. He wasn’t in the habit of talking about his past, at least to his children, but one day, I overheard him telling a visitor about how he used to swim in a river rapid as a young man. He told the story with relish, seeming to plunge once more into the blinding whitewater as he told it.

I was amazed. It was not a side of him that I’d ever seen or suspected. He was in his 40’s by the time I was born; I’d known him only as a hardworking, cautious man of simple domestic pleasures.

When I sat down to write this novel set in 1924, my most vivid impression of life in China during those days was my father’s story about swimming that river. So I began the narrative with my teenage protagonist thinking back to his own attempts to brave chaotic waters:

I picture yesterday’s river,

outside the village that was once

my home, beyond the grove

of dove trees with their long blossoms

hanging like wrinkled paper bats,

the river our parents

forbade us to swim, where we’d plunge

into the churn, blinded by cold

and the bright froth, propelling ourselves,

crossways to the current,

to rise, arms lifted, shivering,

on the rocks of the far side.

My father was an herbalist. My strongest childhood memories involve the smell of the herbs he stocked and the teas he brewed with them, the clanking of the bottles my mother washed, filled with the teas, and then packed into paper bags for his patients, and his heavy footsteps as he walked back and forth between the kitchen and the front part of the house that he used as an office.

And the touch of his fingers on my wrist taking my pulses, his method of diagnosing a person’s health.

Early in the novel, the Chinese detainees are put through medical exams that are traumatizing to them because of how unused they are to western medical practices. In this poem, I contrast that experience with my protagonist’s memories of the doctor who served his village:

my heart

The house

of our village doctor was filled

with the dried-out smell

of root and leaf and twig,

or sometimes with steam

from the teas he brewed, bitter

with potency.

He diagnosed our illnesses

through nothing more

than his touch on our wrists

as we sat across a narrow table made

of a hard, lustrous wood carved

with designs of flowers

and dragons, fancier

than anything else

in the village, but whose fourth leg

was a plain wooden stump.

Sow Fong tells me

the exams we underwent,

the needles

and the nakedness, are just

how medicine is practiced here

and not some special torment

the pale powers reserve

for those they see

as livestock.

Not, he adds,

that they don’t

see us as livestock.

I’m lying

on my upper bunk. We’ve been

to breakfast, but I came right back

and have no wish (for now

at least, I tell

Sow Fong) to be shown

any more

of the barracks or to go

outside.

Sow Fong stands

at the very end

of the bunk. His shifting feet

come close to tripping

over mine, as he tests

how far along

the upward sloping ceiling

he can touch.

Maybe it’s for

the best, he says. It’s

probably better,

right? I’m sure

we’ll get used to it

soon enough.

I think of the man

that everyone

in the village, elder

to child, calls “Doc,”

my wrist on the worn

cloth pad he sets

on the wooden table

between us (the pad

that smells—I smelled

it once, when he

was out of the room, holding

its softness up

to my face—like

the skin and sweat

of everyone else

in my village),

and he’s asking me

how I’ve been eating,

sleeping, with utmost tact

how I’ve been shitting.

I tell him all, feeling

his fingers, soft

as a warm breeze, precise

along my veins, learning

all he needs to know

from the beating

of my heart.