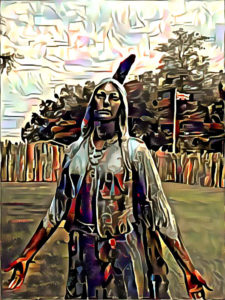

On this day of the March For Our Lives, I’d like to share an excerpt from my current work in progress, Matoaka, a novel of Pocahontas, John Smith, and John Rolfe.

On this day of the March For Our Lives, I’d like to share an excerpt from my current work in progress, Matoaka, a novel of Pocahontas, John Smith, and John Rolfe.

The entire novel is written in the form of prayers by Pocahontas (who is a daughter of the high chief of the Powhatan nation, and whose true name is Matoaka), diary entries by John Smith (one of the leaders of the Jamestown settlement), third person narratives from Smith’s point of view, and letters by John Rolfe, a tobacco farmer who arrives at Jamestown late in the book. In this prayer of Pocahontas, she tells the Great Spirit (“Mother”) about her experience watching one of the Jamestown settlers teaching his son how to shoot a gun. (Some background: MIghty Oak is a native child who is thoroughly steeped in the culture of his fairly militaristic tribe. June is a settler who has shared her oil paintings with Pocahontas. The various parents mentioned — of Pocahontas, Mighty Oak, and Jackrabbit — were all hard on their children in various ways.)

I wrote this episode on a Saturday afternoon last September and was surprised by how easily it came out compared to other parts of the novel up until then, and how polished and finished it already felt in its initial draft. The next day, we heard in the news about a mass shooting in Las Vegas.

A Prayer of Matoaka

O Mother, I saw a man in the fort teaching his child how to use a gun today. Oh, the sound of their weapons is like thunder that shakes the bones of the earth. And yet, the man was a kindly father, and his son delighted in the lesson, I do not think for love of the gun, but of his father. I thought of Mighty Oak’s mother and Jackrabbit’s father, who loved their children. I thought of my father.

The man looked up and saw me watching, and smiled and waved, and instructed his son to wave. I had met him before, in the parlor of June’s house, and I wondered if he imagined aiming his gun, and teaching his son to aim the gun, only at deer and rabbits and geese, or if he understood that if our peoples were to resume their warfare, he would be aiming it at my friends and kin, or at me.

Mighty Oak stood by me and spoke as he had been taught.

“Their weapons are better than ours in some ways, and not as good in others. Their bullets strike more powerfully than any arrow, and can more readily pierce a shield or kill in a single blow. And I have seen how the noise of them frightens many of our warriors, though I myself have never flinched to hear it. A gun can be fired from behind cover; you must expose yourself to shoot an arrow. However, a gun takes too long to fire — I could shoot ten arrows in the time it takes them to prepare a single shot — and arrows can fly farther, and with greater accuracy.”

I walk again beneath the stars, so close and so clear, and yet in truth impossibly distant, and see again in the darkness, as if June had painted a picture of them, the man and his son in their happiness, so like the happiness of any parent and child: my father and I on our walks by the river, Jackrabbit’s father holding his cooing infant son, Mighty Oak struggling to draw his first bow, aided by the encouragements of his mother.

The man kneels and holds the gun up to his son to show him its mechanism, though the boy’s eyes stray often to his father’s face.

He points to this and that part of the gun, speaking and gesturing to his son, who nods and nods.

He leads his son through the pouring of powder and the sliding of a rod down the tip of the gun, praising him as he accomplishes each step, clapping him on the shoulders when they have done.

He gives the gun over to the boy, and crouches behind him, guiding him in holding and aiming it, embracing them both.

And then the gun’s thunder splits the sky.